Satellite symposia have been a hot topic since the American College of Cardiology announced in 2011 it would no longer allow other CME organizations to provide certified continuing medical education satellite symposia at its Annual Scientific Session. That same year, Elizabeth Yarboro, then associate vice president at the ACC and an Industry Alliance for Continuing Education and Medical Specialty Society Collaborative Workgroup member with the Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions, posed a question to the group: How were CME providers and commercial supporters handling satellite symposia? These are, generally speaking, independently organized educational activities that are held in conjunction with a medical association or other organization’s main conference.

It was a good question. There wasn’t much information on best practices for satellite symposia. Was ACC’s situation unique, or were other organizations facing a similar struggle balancing quality and content integrity? The more the workgroup inquired, the more other stakeholders wanted to know.

Unexpected Insights in Stakeholder Data

For nearly three years, the workgroup conducted polls, interviews, focus groups, and stakeholder meetings to determine both the impact of satellite symposia on medical meetings, and the impact of medical meetings on satellite symposia. The group quickly realized that the ACC was not alone, but it was also apparent that stakeholder data held some unanticipated insights.

Early in the assessment phase, the group surveyed commercial supporters, medical communication companies, hospital and healthcare providers, medical specialty societies, and other types of healthcare-related organizations on their barriers to supporting or administering satellite symposia. Commercial supporters were the only group that listed providing “educational value when compared to annual meeting scientific sessions” as a primary barrier to supporting symposia. MSS groups were more concerned with costs. Honestly, we expected the results to show the opposite.

Additionally, while many expressed concerns about conducting satellite symposia, the symposia themselves were alive and kicking. Fifty-seven percent of providers were offering satellite symposia, and one-quarter of supporters estimated that up to half of their entire medical education budget would be spent supporting satellite symposia. Money was flowing in—and societies were counting on it. When surveyed about the financial impact of symposia to their overall program, most organizations identified the revenue stream as modestly important, and 13 percent stated that revenue generated through symposia was “absolutely crucial for the success of our annual meeting.”

Most organizations cannot afford to follow in ACC’s footsteps and remove symposia from their meetings. So the question of how to administer them remains.

The “4+1 Model” of Satellite Symposia

The workgroup’s research didn’t find any best practices for hosting these symposia. Too many departments with too many policies are impacted within each organization to catalog how organizations administer these events.

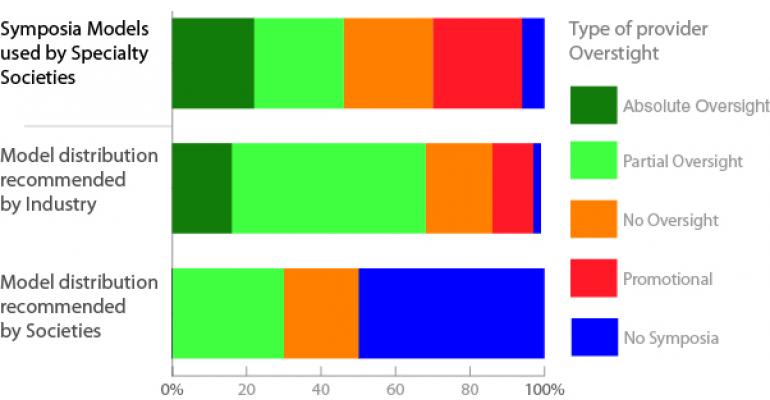

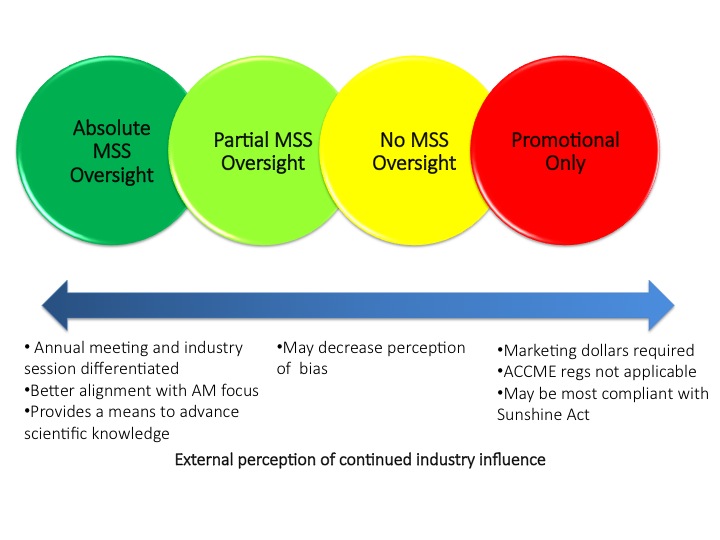

But each group’s practices can be classified on an oversight spectrum from “absolute oversight,” where the society plans and implements a separate activity that they seek support for, to hosting non-certified “promotional only” activities, with partial to no MSS oversight falling in the middle.

With absolute oversight, it’s easier for the MSS to align the symposia with the annual meeting’s focus and provide a means to advance scientific knowledge. It does make it more of a challenge for the MSS to ensure the satellites’ industry sessions are differentiated from those of the annual meeting.

With absolute oversight, it’s easier for the MSS to align the symposia with the annual meeting’s focus and provide a means to advance scientific knowledge. It does make it more of a challenge for the MSS to ensure the satellites’ industry sessions are differentiated from those of the annual meeting.

Partial to no MSS oversight can bring the benefit of decreasing the potential for the perception of bias in the content.

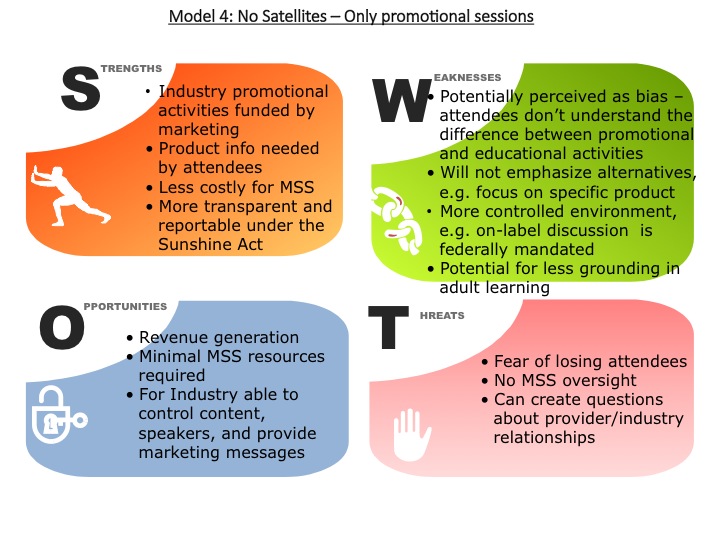

Promotion-only symposia, which are funded from a company’s marketing department, are not subject to Accreditation Council for CME regulations, though they do have to obey the physician tracking and reporting requirements of the Sunshine Act.

This oversight spectrum evolved into the “4+1 Model,” where “4” represents four strata of provider oversight, and “+1” represents those organizations, like ACC, that do not offer any form of symposia. Each model faces distinct challenges, but there is a good deal of overlap within practices. In 2012, the group dove deeper into those similarities and differences for the 4+1.

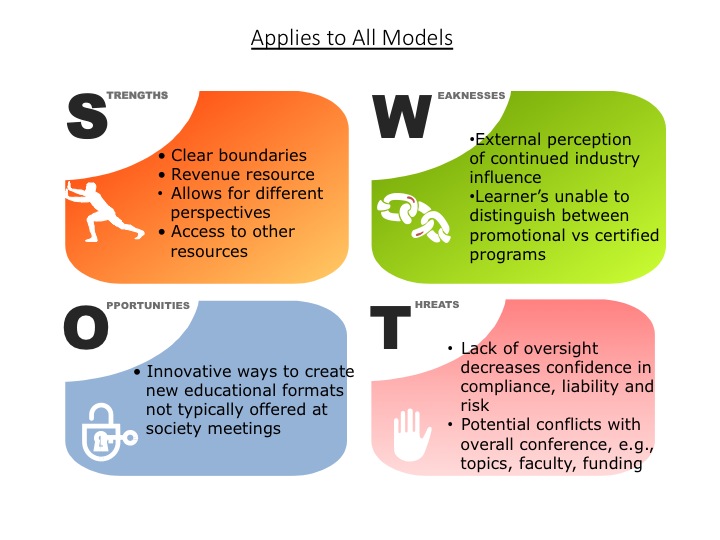

The Story In SWOTs

We surveyed groups of providers and held focus groups to develop SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis for each model.

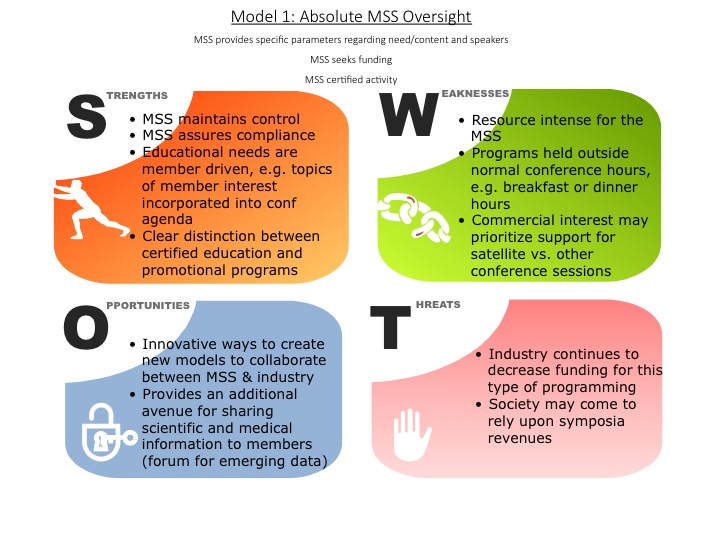

Model 1: Absolute MSS Oversight SWOT

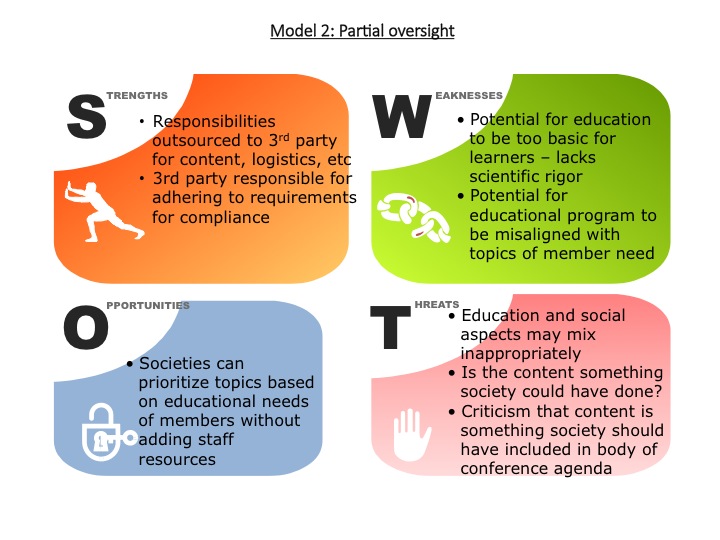

Model 2: Partial MSS Oversight SWOT

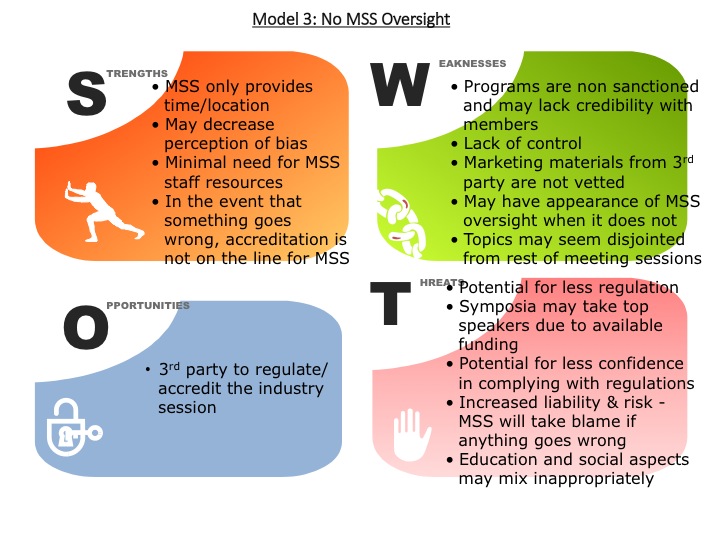

Model 3: No MSS Oversight SWOT

Model 4: Promotional Only SWOT

No single model emerged as “the best”; it’s up to each provider to figure out the balance that works for them. We did find a schism between the model supporters prefer and the model specialty societies are comfortable with:

Societies who once occupied the “middle ground” of partial to no oversight now see these models as higher risk and more difficult to manage. As a result, organizations are moving to the extreme ends of the 4+1 with providers becoming much more involved in symposia planning, or recusing themselves completely from educational components.

Jacob Coverstone, a member of the IACE/MSS Collaborative Workgroup, is director of education with the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine & Section for Magnetic Resonance Technologists in Berkeley, Calif. In addition to attempting to determine what (if any) best practices exist for hosting satellite symposia, the IACE/MSS Collaborative Workgroup members have tackled the standardization of CME-centric language, established a budget template for CME planning and grant requests, and are currently working on a guidebook for grant submission process.